Naval Biomimicry: When the Sea Whispers to Naval Architects

Nature as a Guiding Principle: Biomimicry in Naval Design

Biomimicry isn’t just a laboratory discipline; it’s a mindset, almost a philosophy. The core idea is to understand how living organisms adapt to extreme conditions and then translate those solutions into human engineering. This approach is particularly relevant in the naval world, where the sea presents a hostile environment with winds, waves, salt, and marine organisms constantly challenging anything that floats.

For naval architects, nature is an inexhaustible library. Every fish, shell, or marine mammal holds solutions perfected over millions of years of evolution. Researchers analyze shell shapes to strengthen hulls, scrutinize fish swimming techniques to optimize propulsion, and study natural anti-adhesive surfaces to create coatings that prevent the accumulation of algae and shellfish. In design offices and shipyards alike, a ship’s design is no longer solely dictated by calculations but by a careful interpretation of nature’s strategies.

Unlocking Secrets from Coral, Sponges, and Fish

Coral reefs, for example, are true natural fortresses. Their network structure dissipates wave energy while offering remarkable resistance to erosion. This principle inspires coastal defenses and even hulls capable of absorbing shocks by distributing forces. Marine sponges, on the other hand, possess a silica skeleton organized to combine lightness and strength, a valuable model for designing more resilient ship structures without adding weight.

Fish also impart their wisdom. The tuna, a champion of speed, adopts a streamlined shape and fins that minimize drag. This hydrodynamics directly inspires faster hull profiles that consume less fuel. Surprisingly, dolphin skin, which inhibits the proliferation of algae and microorganisms, serves as a reference for developing non-toxic marine coatings. Where old antifouling paints used harmful substances, bio-inspired solutions rely on texture to discourage adhesion, without polluting the water.

Flying Underwater: The Flying Fish’s Fascination

Among the marine creatures that excite the imagination of architects, the flying fish holds a special place. This small animal, capable of leaping out of the water and gliding for tens of meters, combines muscular power, hydrodynamics, and lift. Its long pectoral fins, deployed like wings, function as natural foils.

This observation has led some designers to rethink how boats use their appendages. The idea is to draw inspiration from the seamless transition between swimming and flying in the flying fish to optimize the foils of racing sailboats and, eventually, pleasure craft. Such an approach could significantly reduce drag in the water and increase cruising speed, while offering better stability in rough seas. More than a biological curiosity, the flying fish becomes a design guide, capable of reinventing the relationship between the boat and the water’s surface.

Undulating to Capture Energy: The Eel’s Contribution to Marine Energy

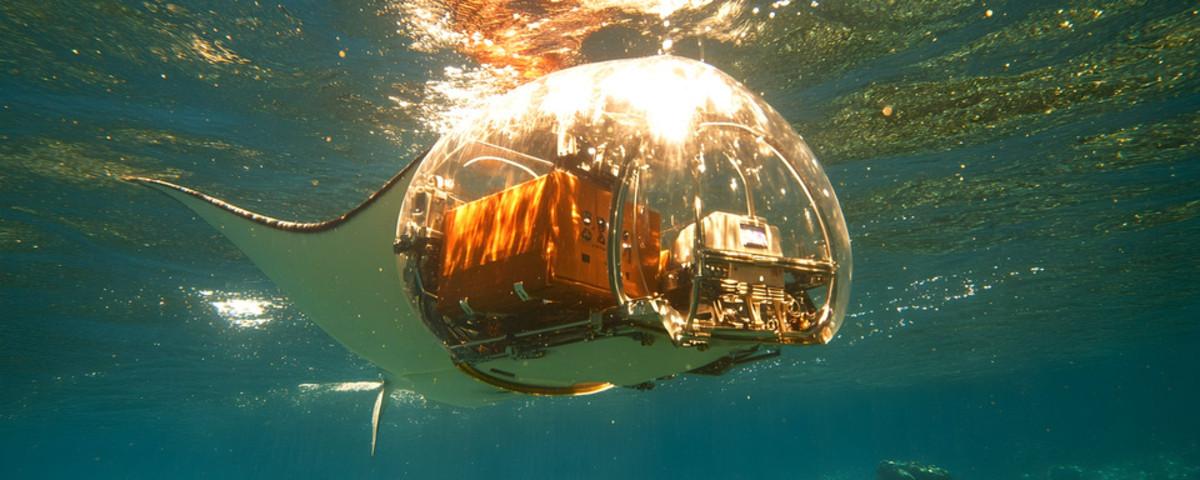

Naval biomimicry isn’t limited to hull shapes; it also affects how energy is produced at sea. The example of EEL Energy perfectly illustrates this. Rather than replicating a propeller or a conventional turbine, their engineers observed the undulation of eels and rays to design a flexible hydro turbine, composed of a membrane that undulates with the rhythm of the current.

This system offers several advantages: it operates at low current speeds, it poses no danger to marine life, and it doesn’t require complex submerged mechanical parts. By mimicking a natural movement, it transforms the kinetic energy of the water into electricity in a more fluid and environmentally friendly way. This technology opens up prospects for powering maritime installations, or even ships, with local and renewable energy, directly drawn from the environment in which they operate.

A Region as a Pilot Zone for a Bio-Inspired Blue Economy

In some regions, biomimicry is seen as an economic driver. These regions are establishing themselves as open-air laboratories for this approach. They support research programs involving biologists, engineers, and naval companies. The goal is to develop solutions inspired by living organisms, tested in real-world conditions, and quickly transferable to industry.

Pilot projects are emerging: anti-adhesive coatings inspired by shark skin, hulls shaped like pelagic fish, wave energy systems… This network of public and private actors allows for the pooling of knowledge and the creation of a sustainable innovation ecosystem. By focusing on biomimicry, the region is not simply following a trend; it is positioning itself as a pioneer of a new way of designing the maritime economy, more resilient and in tune with natural cycles.

Far from being a passing fad, naval biomimicry embodies a true cultural shift in boat design. It’s no longer just about building faster or bigger, but about building better, by listening to the lessons of millions of years of evolution. The shapes, textures, and movements observed in the marine world become technical solutions: clean coatings, optimized propulsion, gentle energy production.

This paradigm shift opens a horizon where performance and respect for the environment advance together. The ships of tomorrow may well be the direct heirs of the flying fish, the tuna, or the eel, and sail not against nature, but with it.

Enjoyed this post by Thibault Helle? Subscribe for more insights and updates straight from the source.